sharing-simulation

Introduction

Purpose of the model

This model is designed to demonstrate the possible cost (in lives lost) of not sharing critical care resources during a pandemic. Its purpose is not to come up with precise numbers that reflect the actual population nor to precisely model the pandemic in a specific state. Instead it is designed to compare the lives lost in imaginary states that are sharing critical care resources with other states, compared to those that are not sharing resources during pandemic surges.

Methods

This is a Susceptible Infected Recovered (SIR) model. Each state has a population of citizens. The pandemic begins with a small number of infected citizens, and initially spreads based on an initial infection co-efficient (R0). Once a certain threshold of infection doubling is reached, the state introduces distancing measures. These measures are implemented after a delay. Once in place, the infection co-efficient becomes the effective transmission during distancing (Rt). Once the number of infections per 100,000 population drops below a threshold, distancing measures are relaxed after a delay, and return to the original R0.

A proportion of the infected patients become severely ill. Mildly ill do not require hospital level care. Moderately ill patients require hospital level care but do not require critical care. Severely ill patients require critical care services, such as ventilation or pressors. Without these critical care services, the patients are expected to die. Only severely ill patients are specifically identified in the model.

Different resource control strategies for assigning critical care beds are included in the model. These include:

- no sharing (that is each state has its own critical care beds only)

- sharing (that is all states that are part of that resource control share all beds)

- limited sharing (that is states that are part of that resource control share beds with other states, only up to a certain limit. For example, a 10% limit would mean that 10% of the beds are always reserved for local use only. Once there are fewer than 10% of beds available in a state, they are not available for out of state transfers.)

Parameters

The data in the model is based on data for the state of Massachusetts.

The state has a population of 4,000,000 people.

Based on the current US average^1^ of 2.77 hospital beds per 1,000 population, and 29.4, this population would have 11,080 hospital beds and would have 1176 ICU beds. Some number of hospital beds can be used as ICU beds. Based on our experience during COVID, we have estimated that 1/3 of hospital beds can be used as ICU beds if needed.

For simplicity, we will assume that the states have equal resources. We know that in reality the number of hospital beds varies from 1.7 per 1,000 in some states to 4.8 in others^2^.

R0 is defined as the R0 that occurred initially in MA = 4.93^3^

Rt is the effective transmission during social distancing = 1.01^4^

The rate of severe illness for infected patients is estimated at 5% based on published data, we have used a conservative estimate of 3.5% in our model^5^. Estimates of mortality from China initially suggested a mortality rate of 1.4%^6^ while those in Italy were up to 11%^7^. We used a conservative estimate of 1% mortality in our model.

Results

Baseline: no sharing

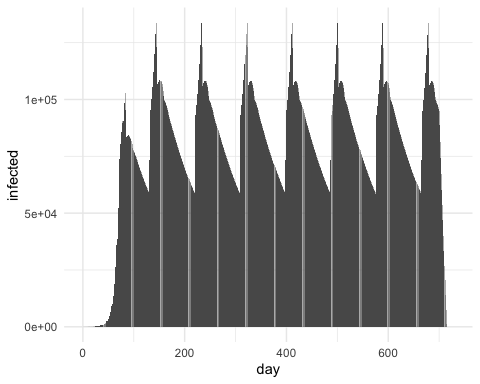

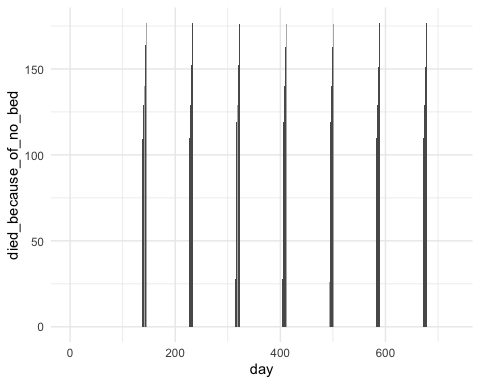

Results for a single state, show the cycles of infection, and the usage of available critical care beds.

Even with our conservative estimates, we can see that during surges, the number of severely ill exceeded the number of critical care beds available. With no sharing the excess mortality of people who will die because there are not enough ICU beds is estimated to be 7,107.

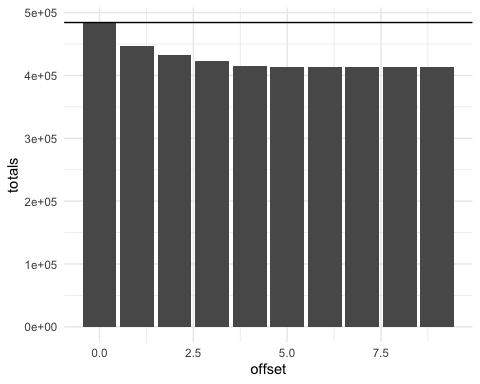

Scenario: 2 states sharing vs not sharing

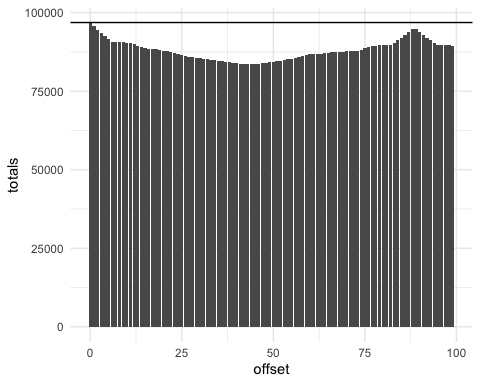

The line shows the lives lost without sharing. Below the line we see the lives lost when there is sharing. The lives saved varies based on how much later the pandemics started (the offset).

When the pandemics completely overlap then no additional lives are saved.

If the peaks do not overlap, the maximum lives saved is estimated to be 13,150.

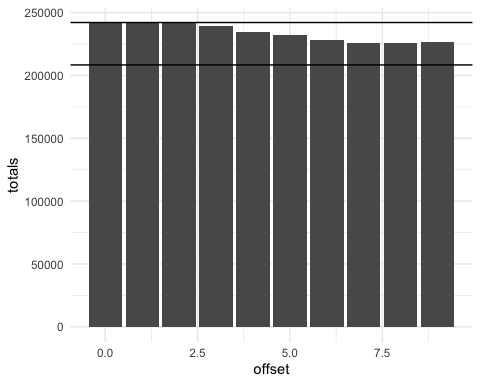

Scenario: 50 states sharing vs not sharing

In the scenario of all states being able to share all resources, the system reaches the optimum (with no lives lost due to a critical care shortage) very quickly.

The lives saved is estimated as 352,049.

Scenario: Regional sharing only (10 states only)

There are unfortunately limits on the distances that most critically ill patients can be transported. This could be overcome by transporting providers and equipment instead so the 50 state scenario with maximal sharing is possible.

To understand what a more realistic scenario of regional sharing and likely regional pandemics would look like, we modelled sharing with only 10 states shared (such as might happen in the NorthEast).

The maximum lives saved for only 10 stated sharing is estimated as 70,405.

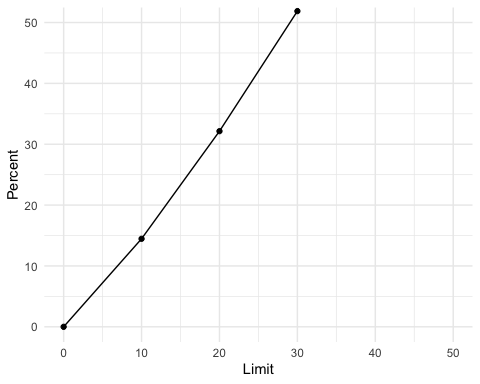

Scenario: Limits on sharing

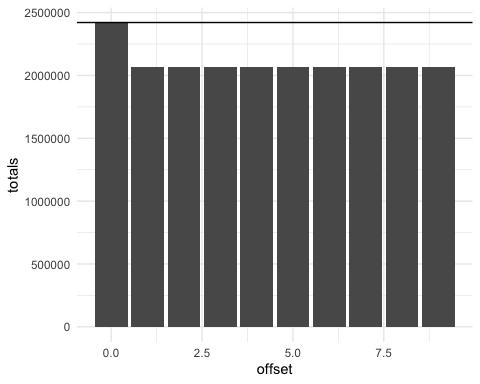

There is a cost in both patient outcomes (in the case of delayed surgeries) and economic costs (in lost revenue) in sharing hospital resources maximally. We therefore modeled the ability for hospitals to limit the number of beds that they share, as described above.

This limits the overall global maximum of lives saved due to a lack of critical care resources, but some of this could be offset by decreased mortality from delays in care (such as delayed surgeries that would require critical care resources after). We do not have sufficient data to be able to model or adjust for this.

The lower line indicates the maximum lives saved with full sharing.

The effect of limiting sharing has a greater than linear effect on worsening mortality across the whole system.

This graphs shows the decrease in percentage of lives saved when a percentage of beds are limited in each state.

Discussion

This simple model of susceptible, infected and recovered within states that have variable infection co-efficients based on distancing or not distancing strategies demonstrate pandemic dynamics. It has allowed us to model possible critical needs for these populations, and to investigate the effect of different sharing strategies on overall and state mortality.

References

^1^ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_hospital_beds

^3^ https://modelingcovid.com/state/MA

^4^ Covid Modelling from Dr Dryden Peterson for Mass General Brigham

^5^ Berlin, David A., Roy M. Gulick, and Fernando J. Martinez. “Severe Covid-19.” New England Journal of Medicine 0, no. 0 (May 15, 2020): null. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp2009575.

^6^ Guan, Wei-jie, Zheng-yi Ni, Yu Hu, Wen-hua Liang, Chun-quan Ou, Jian-xing He, Lei Liu, et al. ”Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China.” New England Journal of Medicine 382, no. 18 (April 30, 2020): 1708–20. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032.

^7^ Boccia, Stefania, Walter Ricciardi, and John P. A. Ioannidis. “What Other Countries Can Learn From Italy During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” JAMA Internal Medicine, April 7, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1447.